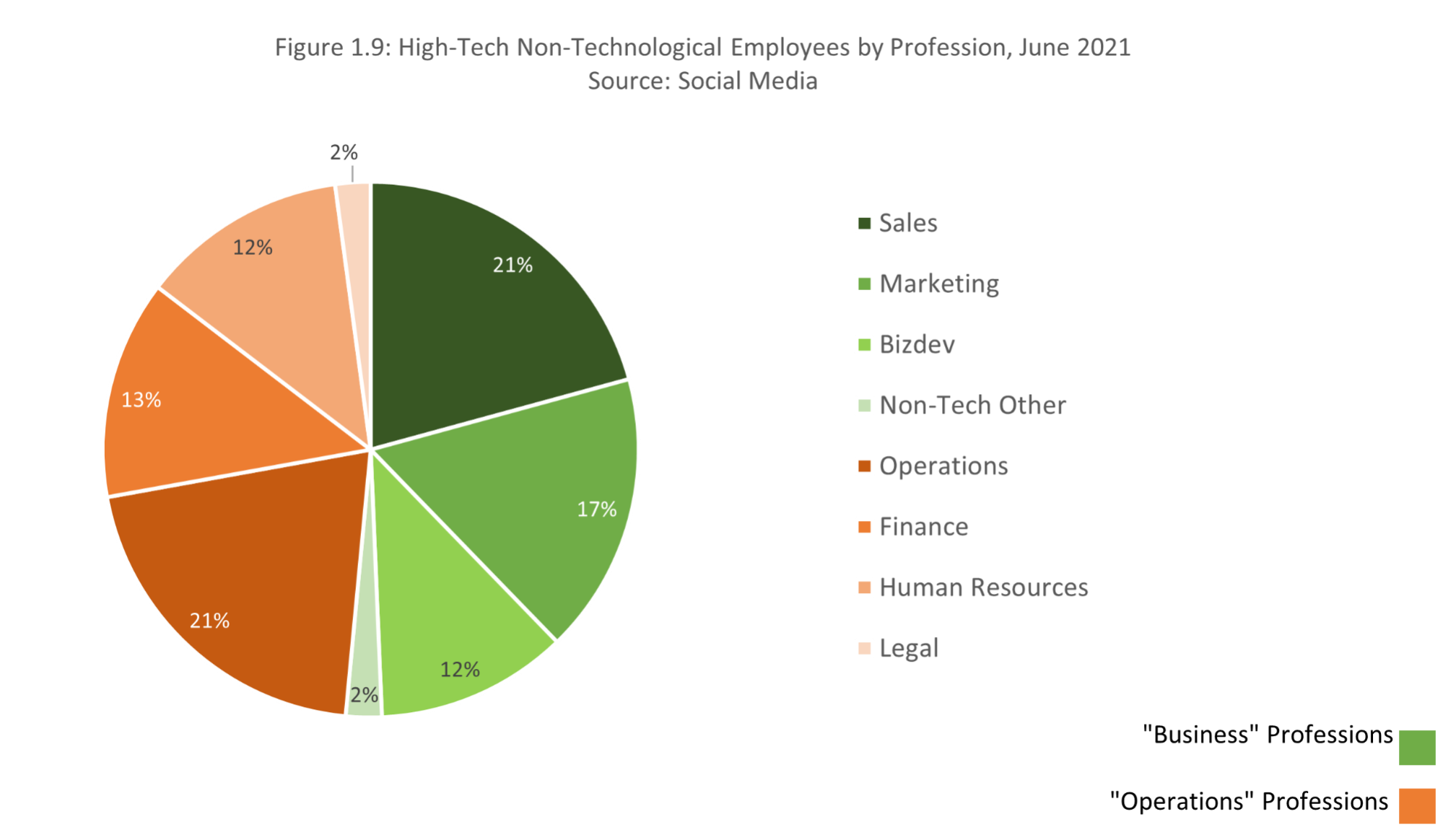

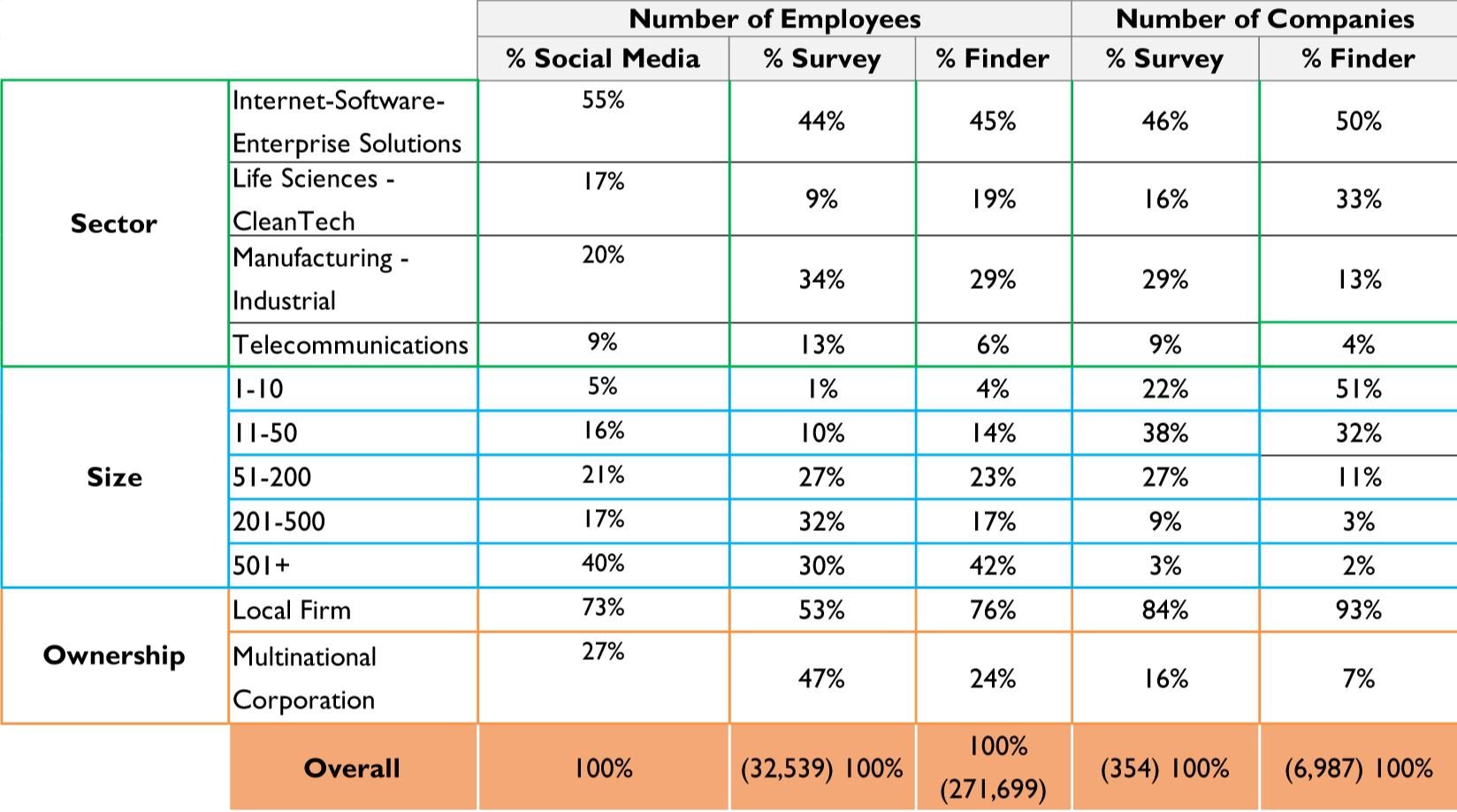

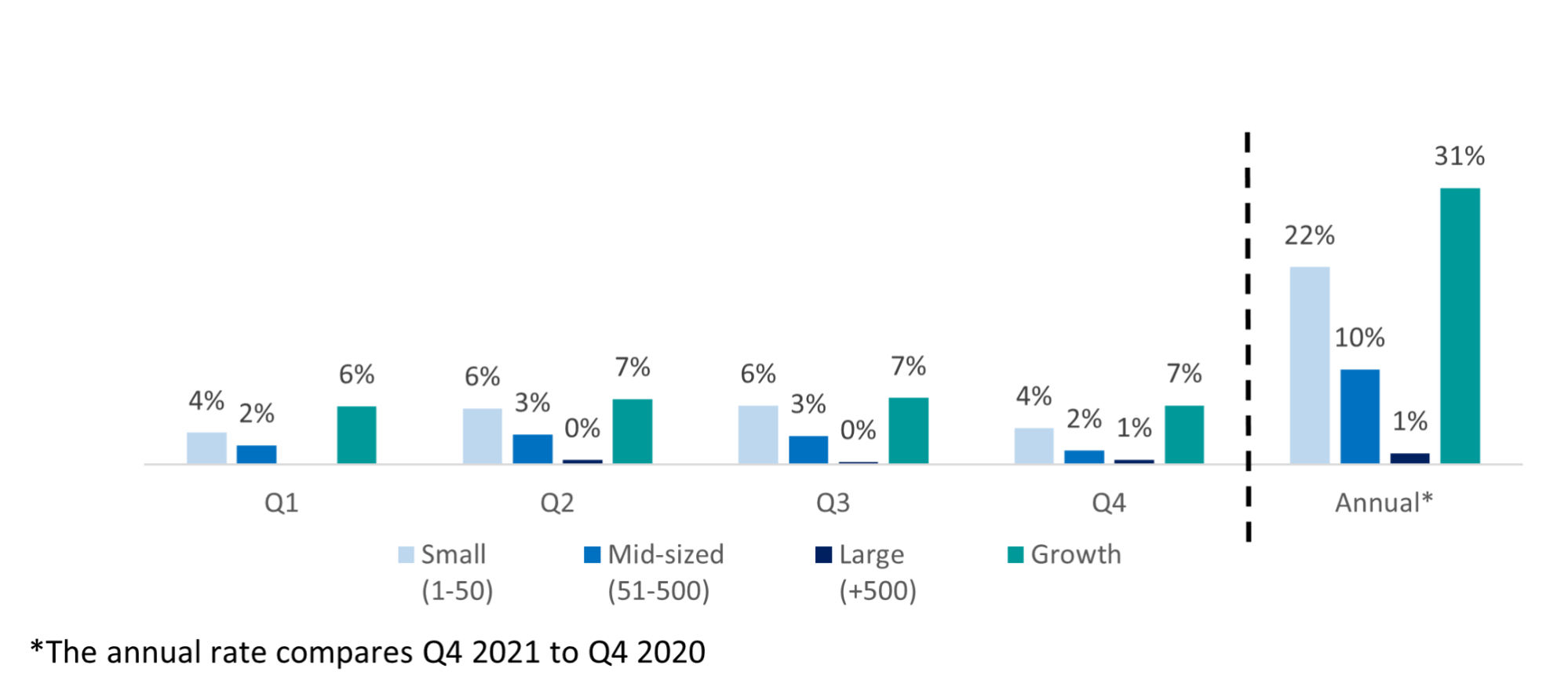

One of the central trends arising from this report is the maturation of the industry, evidenced by the growing share of Israeli “growth” companies. On the one hand, as mentioned, these companies led the growth in recruitment in 2021. That said, they are still relatively young and more sensitive to market volatility. An example of this can be seen in their reaction to the state of the market, expressed in the rate of recruitment for 2020-2021 – a period of crisis followed by a peak year. This segment of the ecosystem is very important to the Israeli economy, as these companies tend to hire across a larger and more diverse array of professions, especially for non-tech roles (35% of employees in local growth companies fill non-tech roles, compared to 20% in the R&D centers of multinational companies). Given the role of the local growth companies in the Israeli economy, it is important to track how they respond to the current crisis developing in the markets.

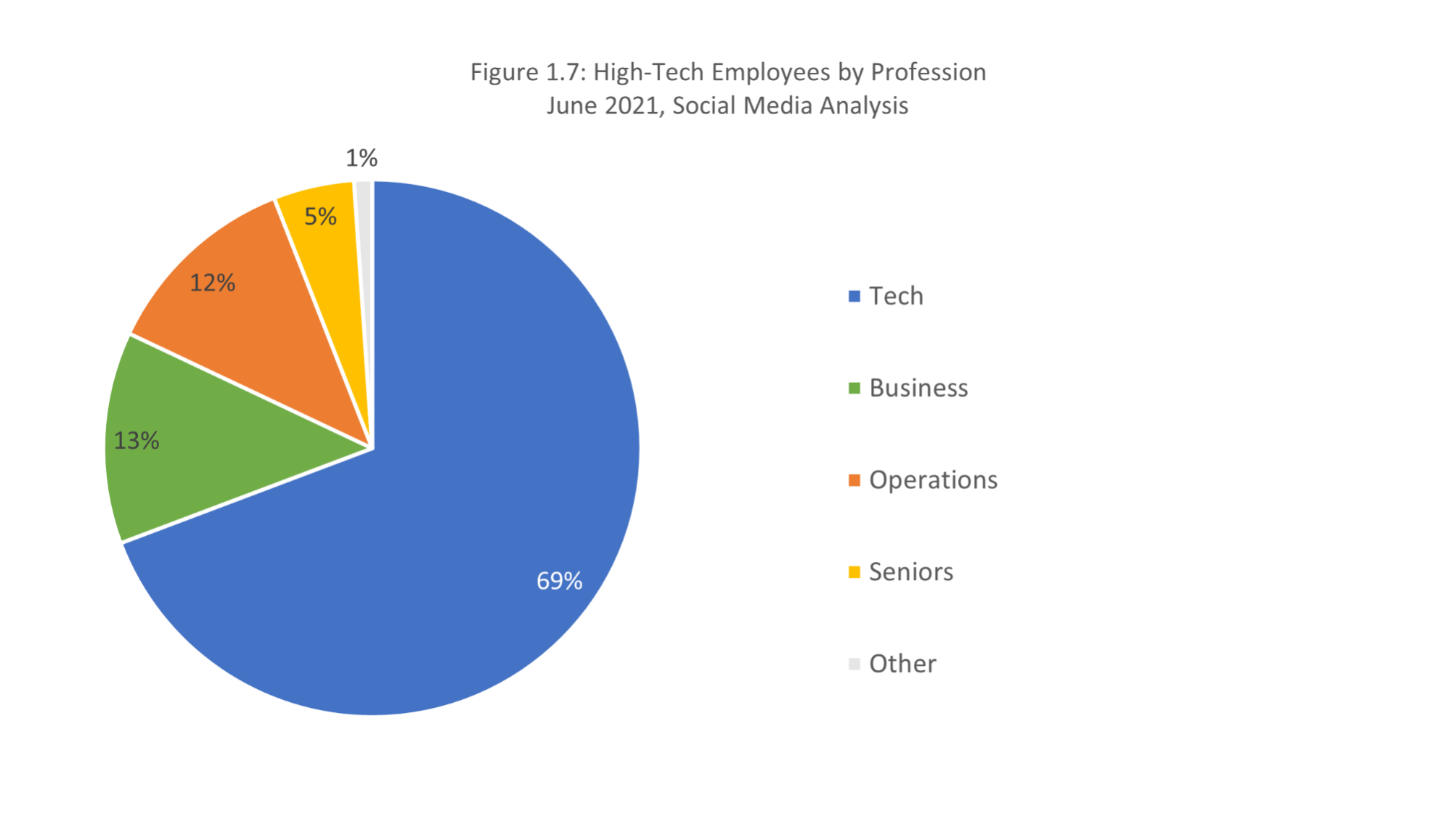

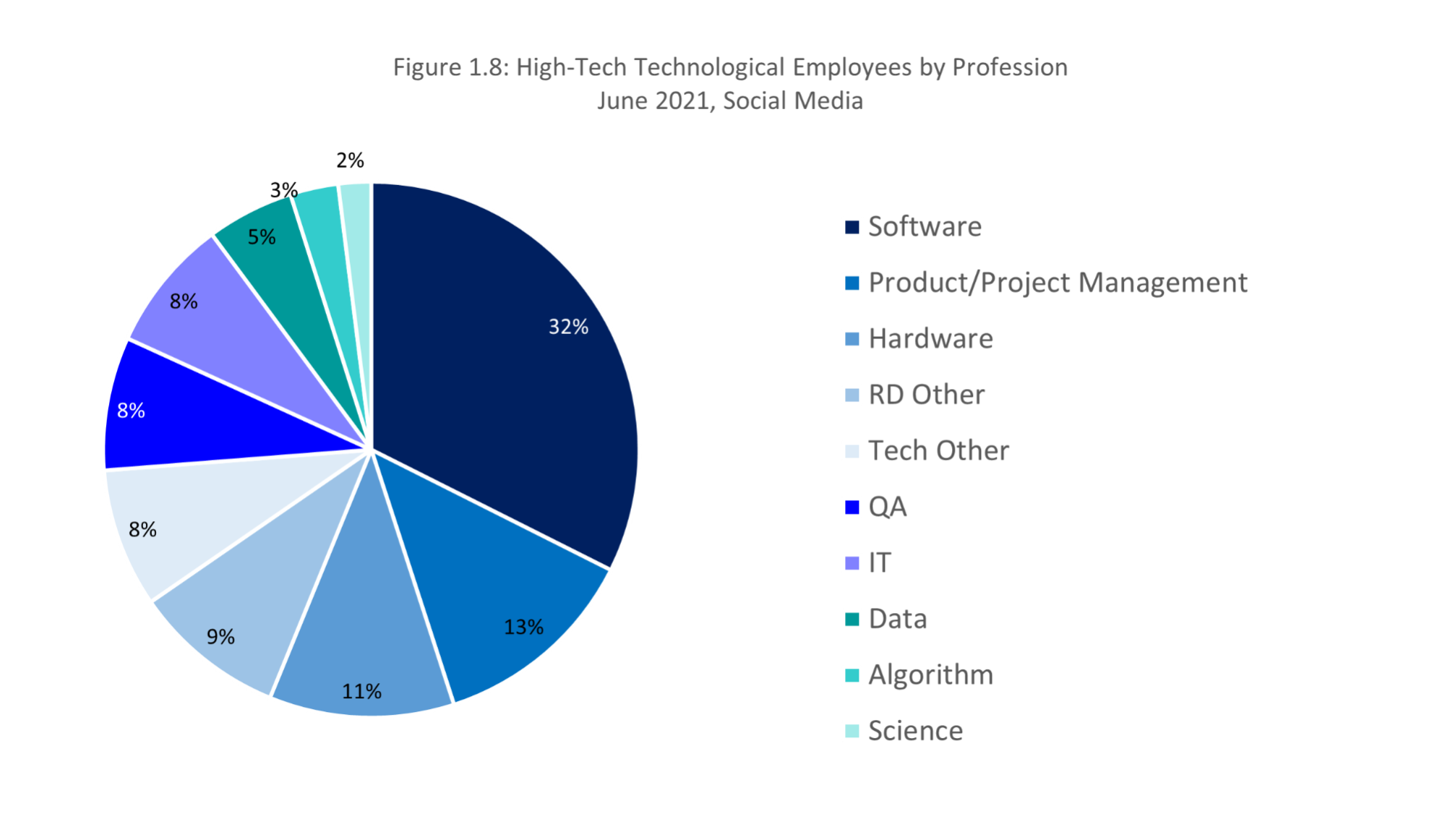

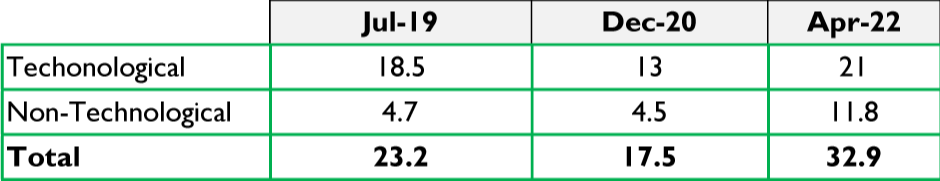

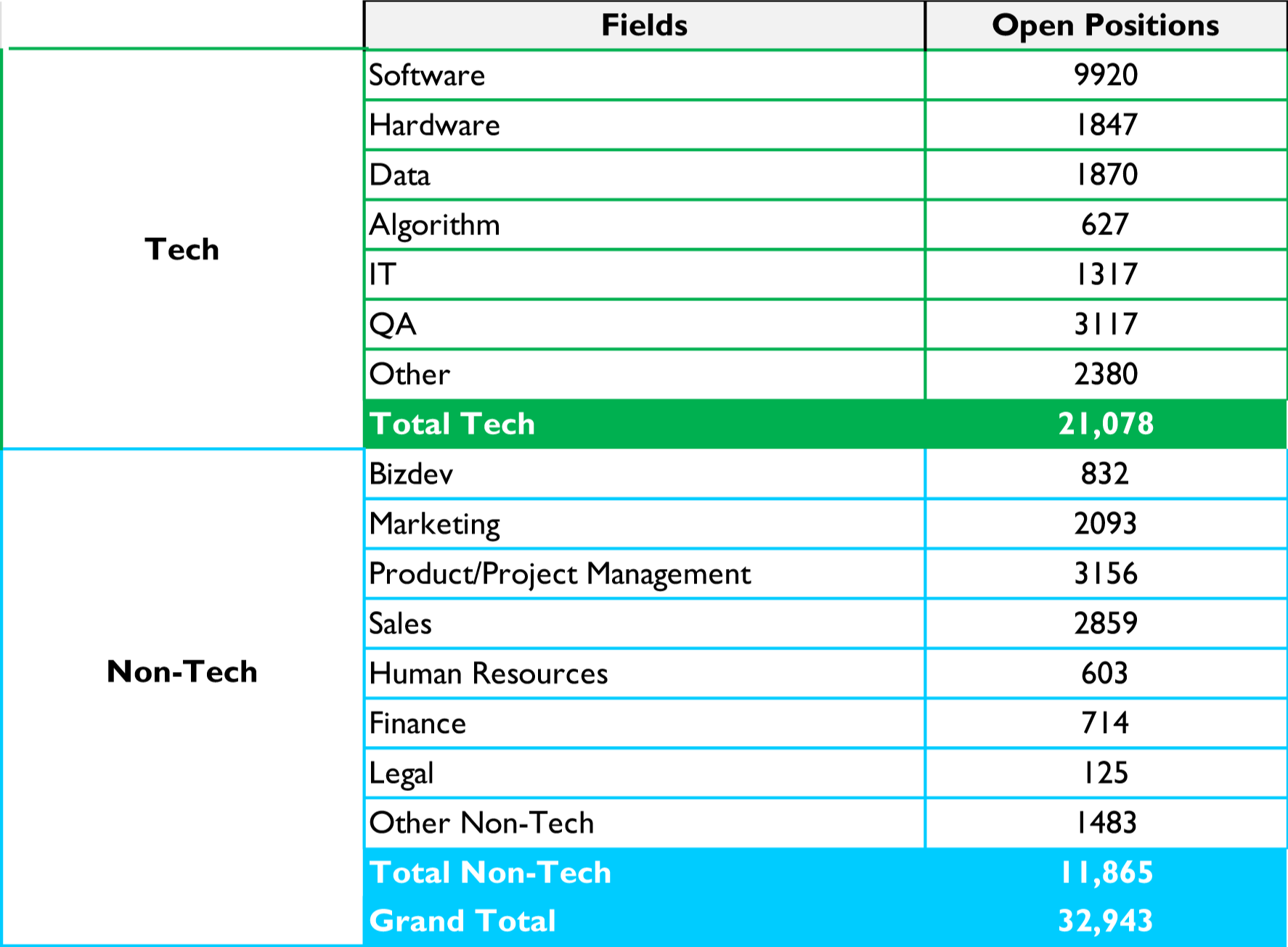

Indeed, opportunities for people without tech training in the Israeli high-tech sector are growing. The data show that the majority of the increase in the number of open positions were for non-technical roles, that increased from 4,500 in 2020 (similar to 2019), to 11,800 – a more than 2.5x increase. This, while the number of open technological roles grew at a slower rate. Alongside this, 70% of high-tech workers are still employed in technological roles that form the core of the industry.

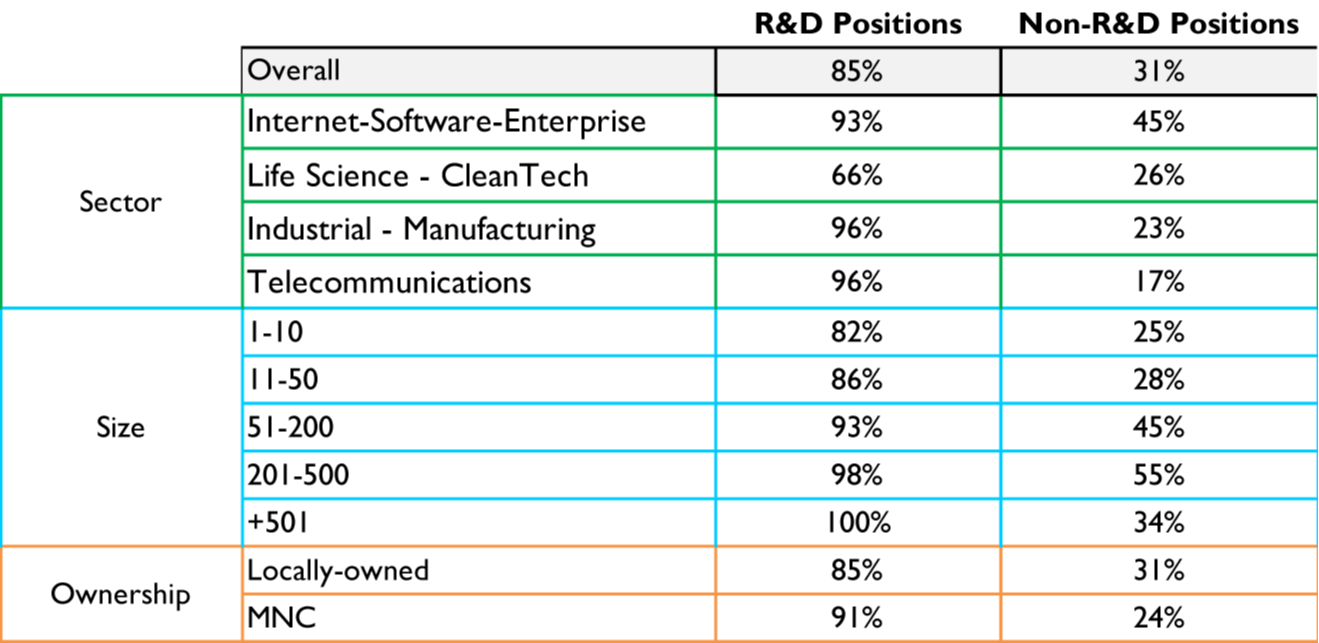

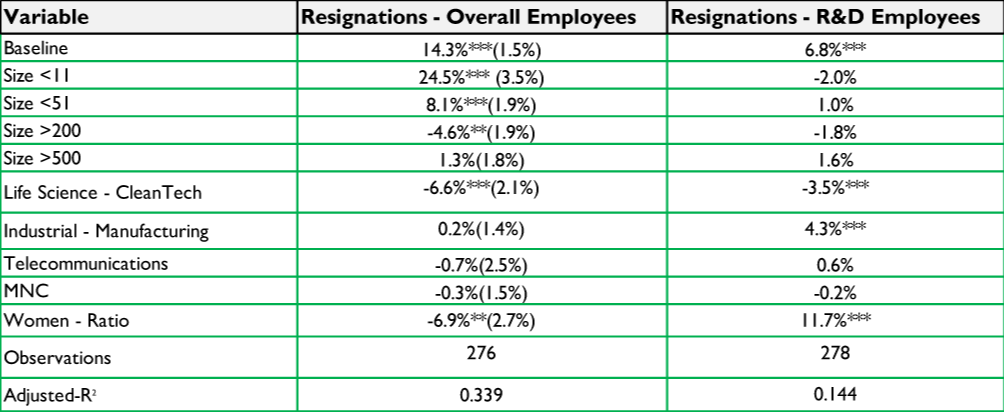

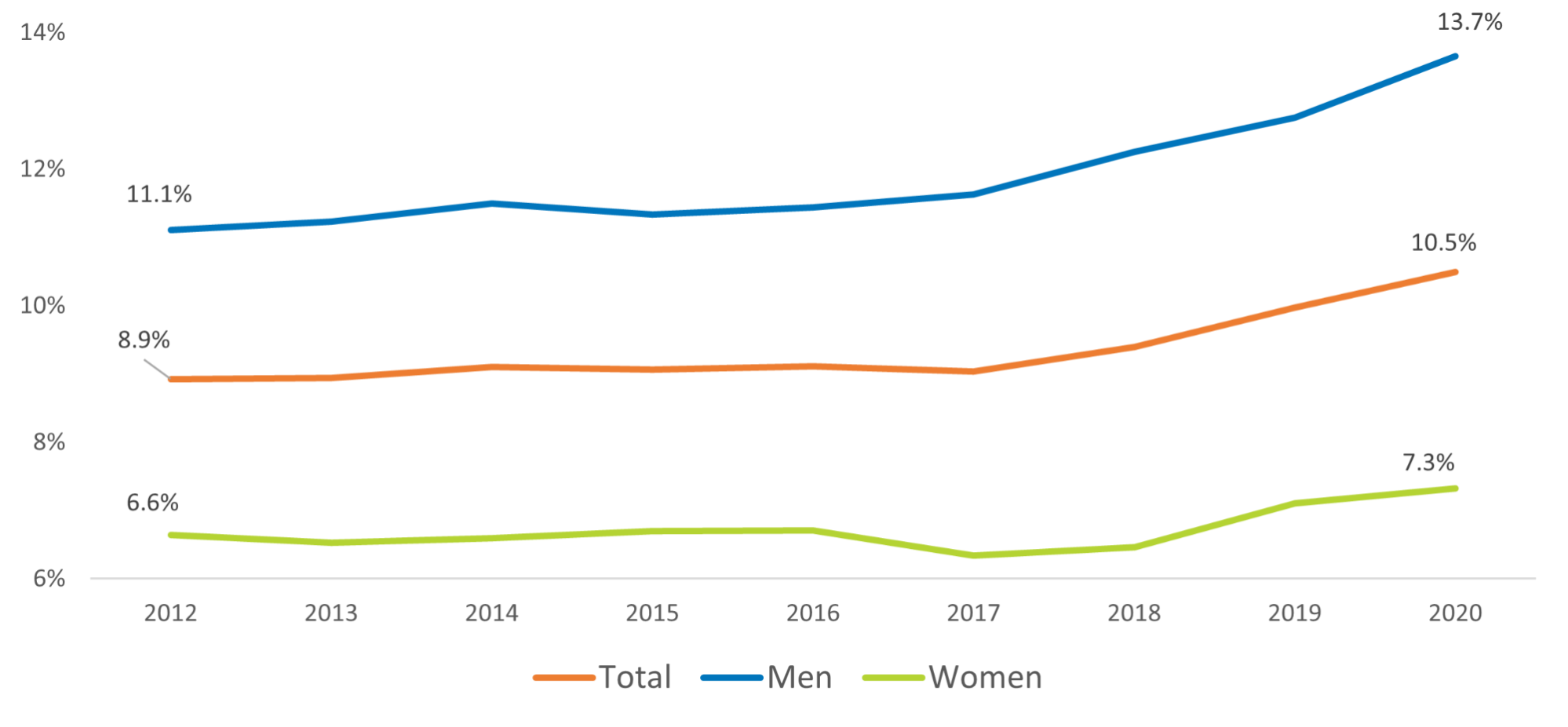

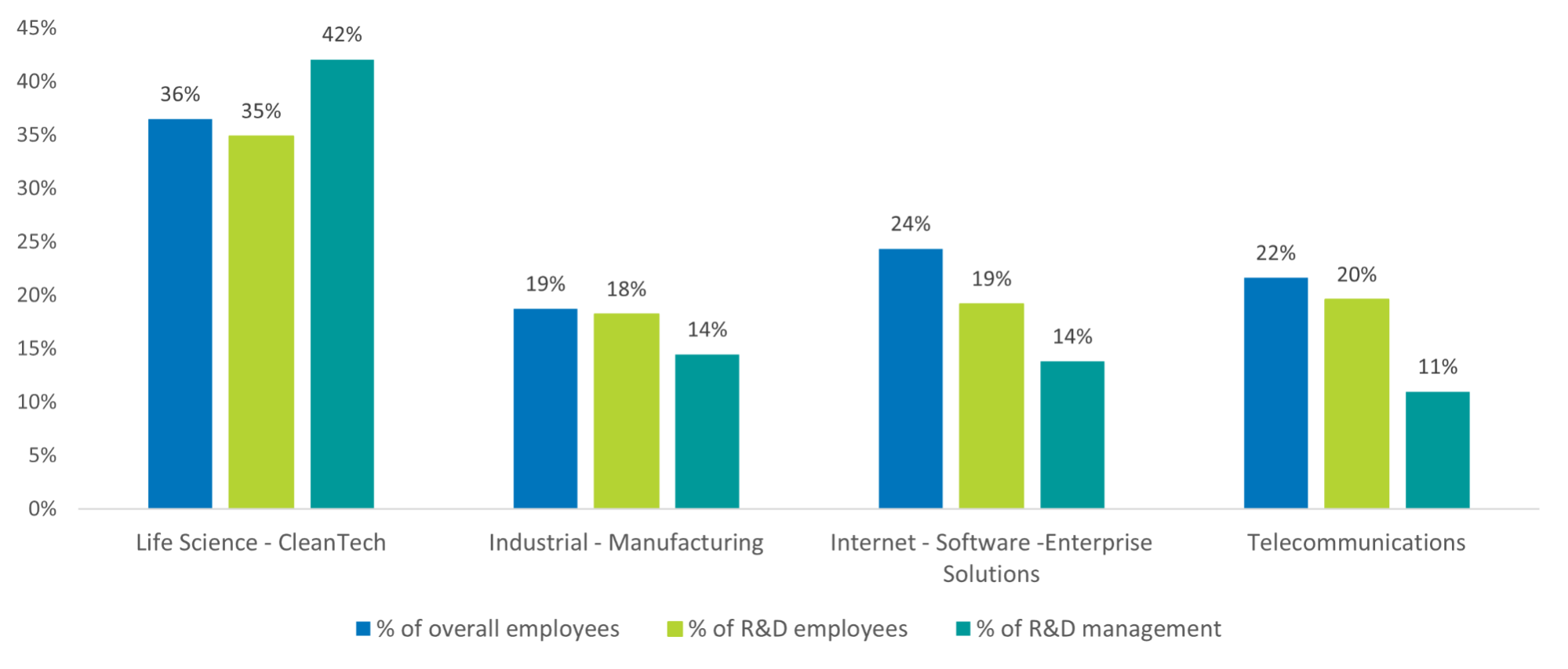

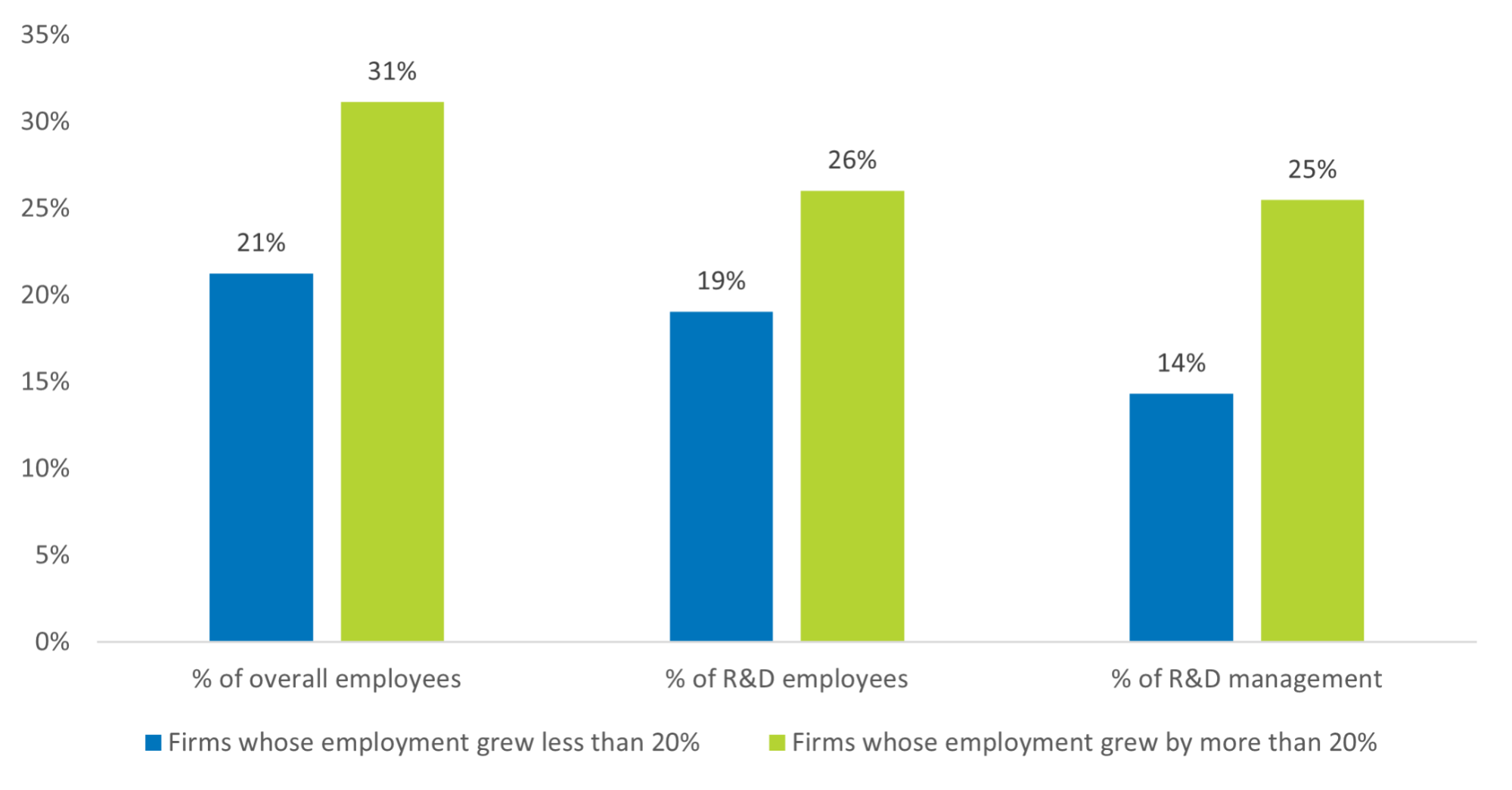

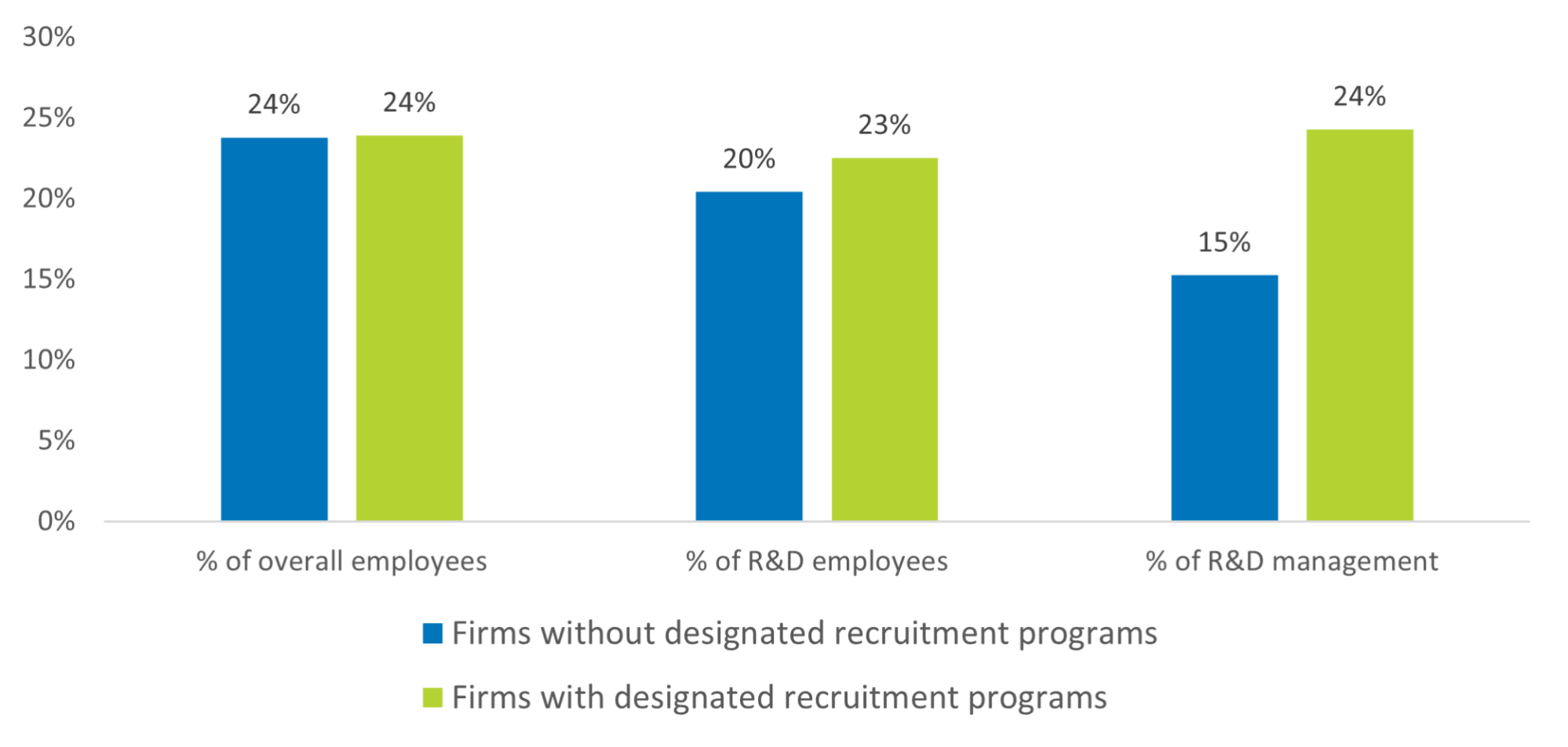

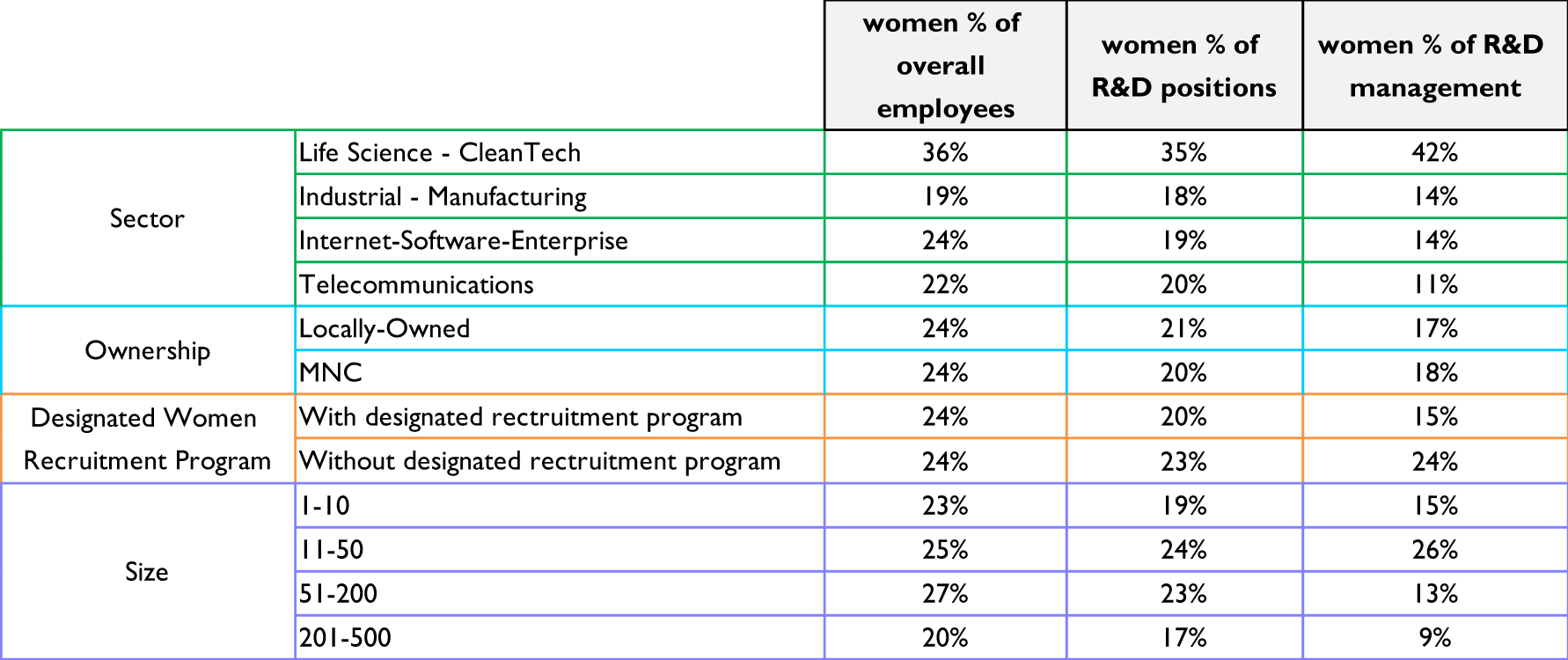

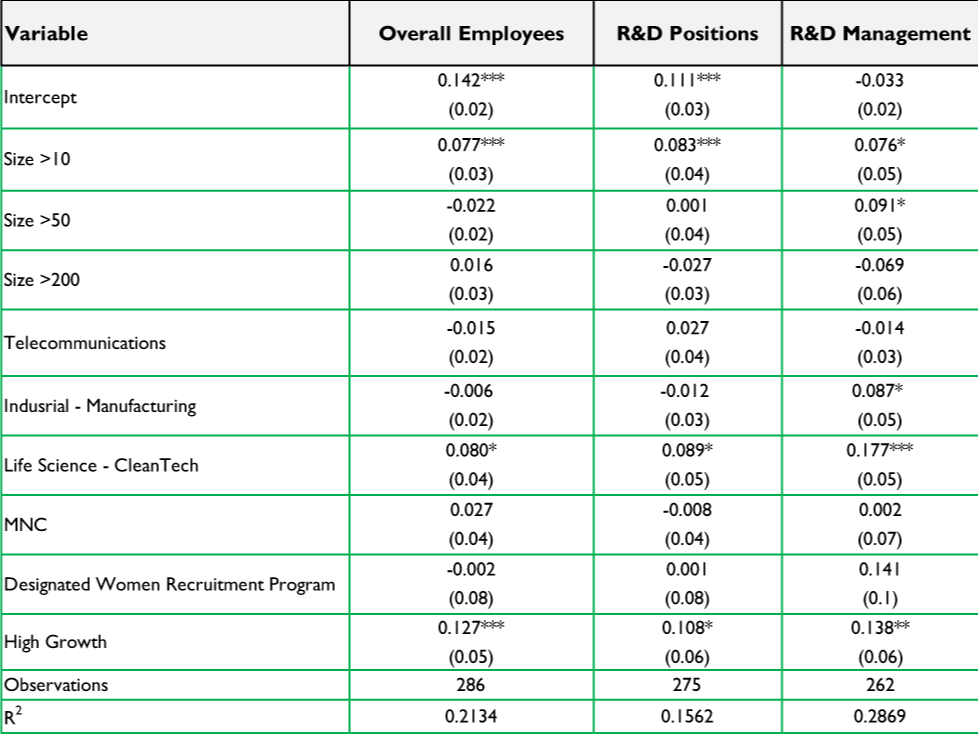

Regarding diversity in high-tech, the majority of its workforce is still overwhelmingly male. Our findings indicate that smaller companies have a lower share of female employees, while companies in the Life Sciences tend to have a higher share of female employees. Multinational corporations also tend to have a higher share of female employees in R&D management positions. Finally, the companies with the highest recruitment rates (above 20%), also tend to have higher shares of female employees.

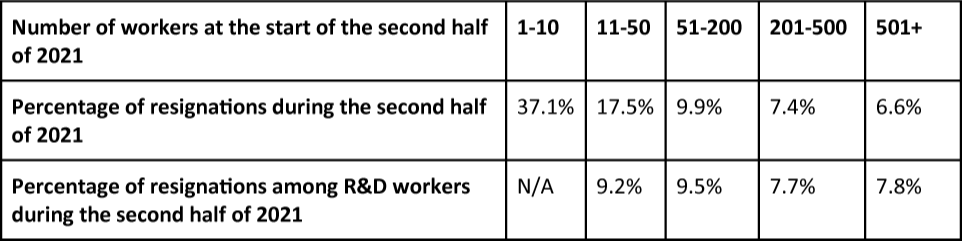

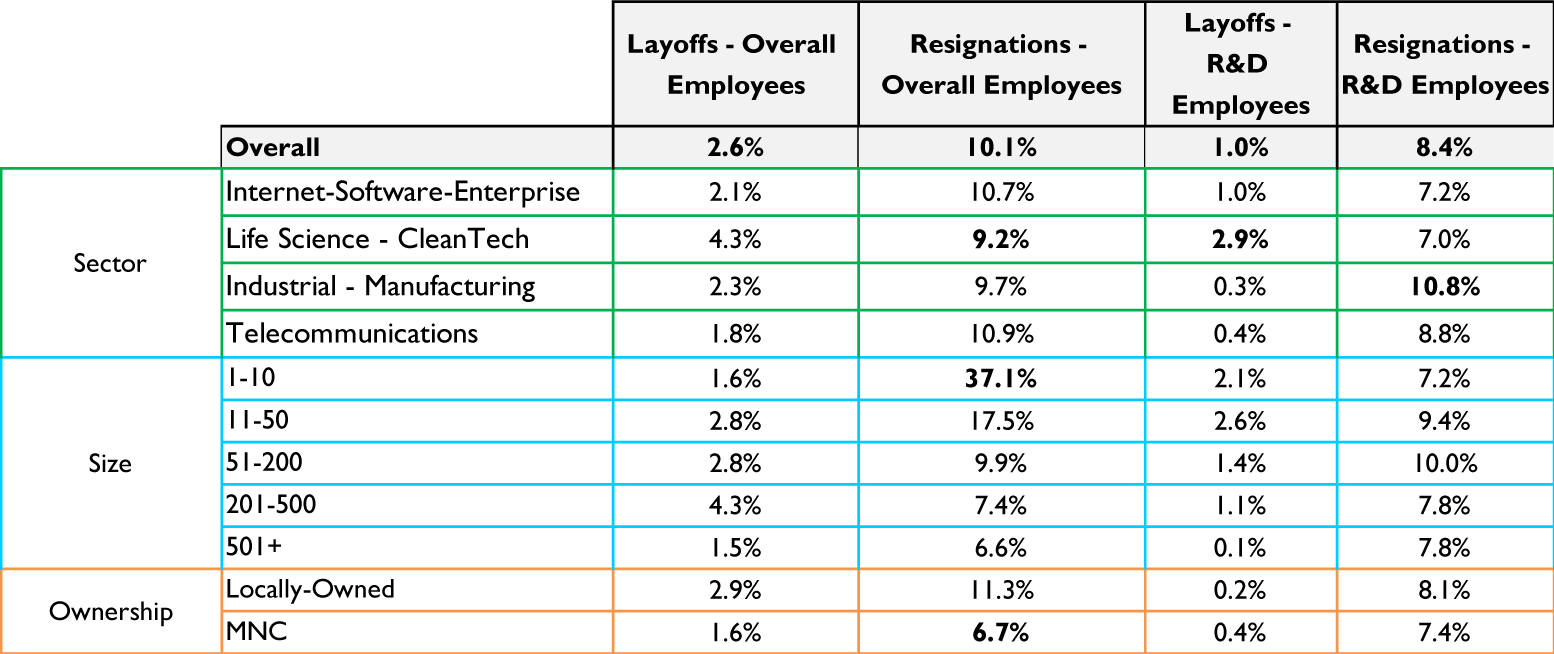

The phenomenon of an “employees’ market” is evidenced by the high rates of voluntary resignations and low rates of layoffs. In H2 2021, 10.1% of high-tech workers resigned – a figure similar to pre-COVID levels. In parallel, a sharp decline of 2.6% was measured in the rate of layoffs – the lowest level in the past decade. Voluntary resignations were most damaging to the smallest companies, especially those with less than ten employees. In H2 2021, these companies lost a third of their employees (the calculation refers to their initial status, but it should be noted that in some cases these companies recruited additional employees concurrently). Alongside this, the Life Sciences and Cleantech sectors had a significantly lower rate of resignations, at 9.2%, despite the fact that most companies in these sectors are small. Finally, the rate of voluntary resignations was significantly lower (by 7%) in companies with a higher share of female employees.

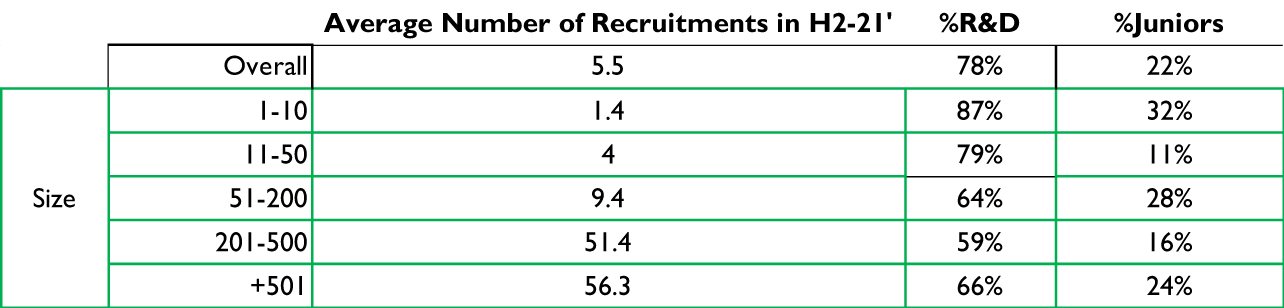

The phenomenon of employees moving between companies indicates both the high level of competitiveness within the industry, alongside the challenge of managing operations despite a transient workforce. It should also be noted that this phenomenon makes it harder for inexperienced workers to enter the industry. An oft-heard claim is that high-tech companies prefer to compete over senior (and more expensive) employees, rather than investing in juniors whose output in early stages is low, out of concern that they will move to a different company shortly after the end of the training period.

Furthermore, the economic literature indicates that in times of recession, companies typically minimize expenditures via layoffs (its easier to fire workers and hire new ones during a recession rather than lowering existing workers’ salaries). Therefore, there is a legitimate concern that should the recession intensify, we may see an increase in the rate of layoffs, mainly of juniors, non-technological workers, and workers with non-academic backgrounds.

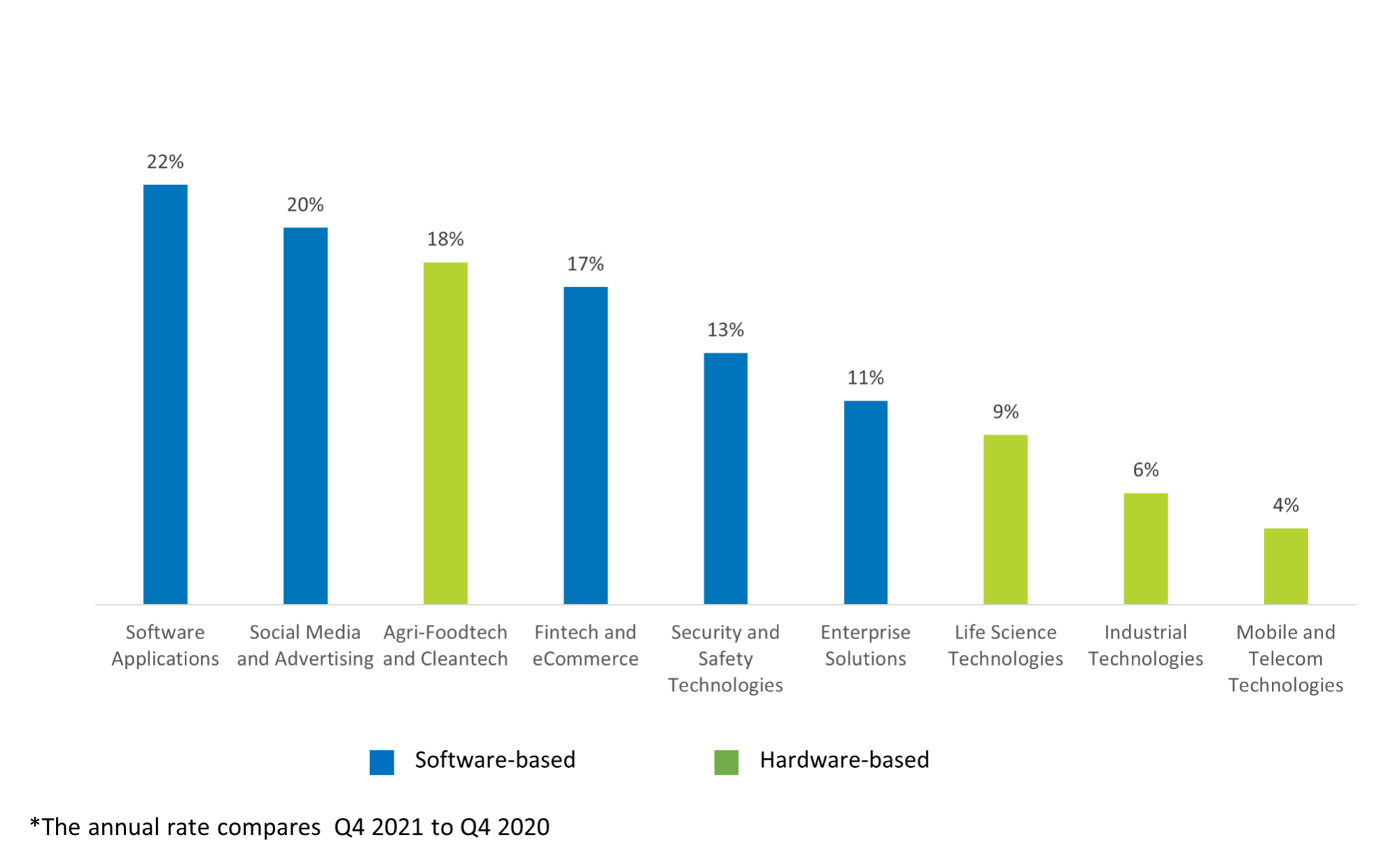

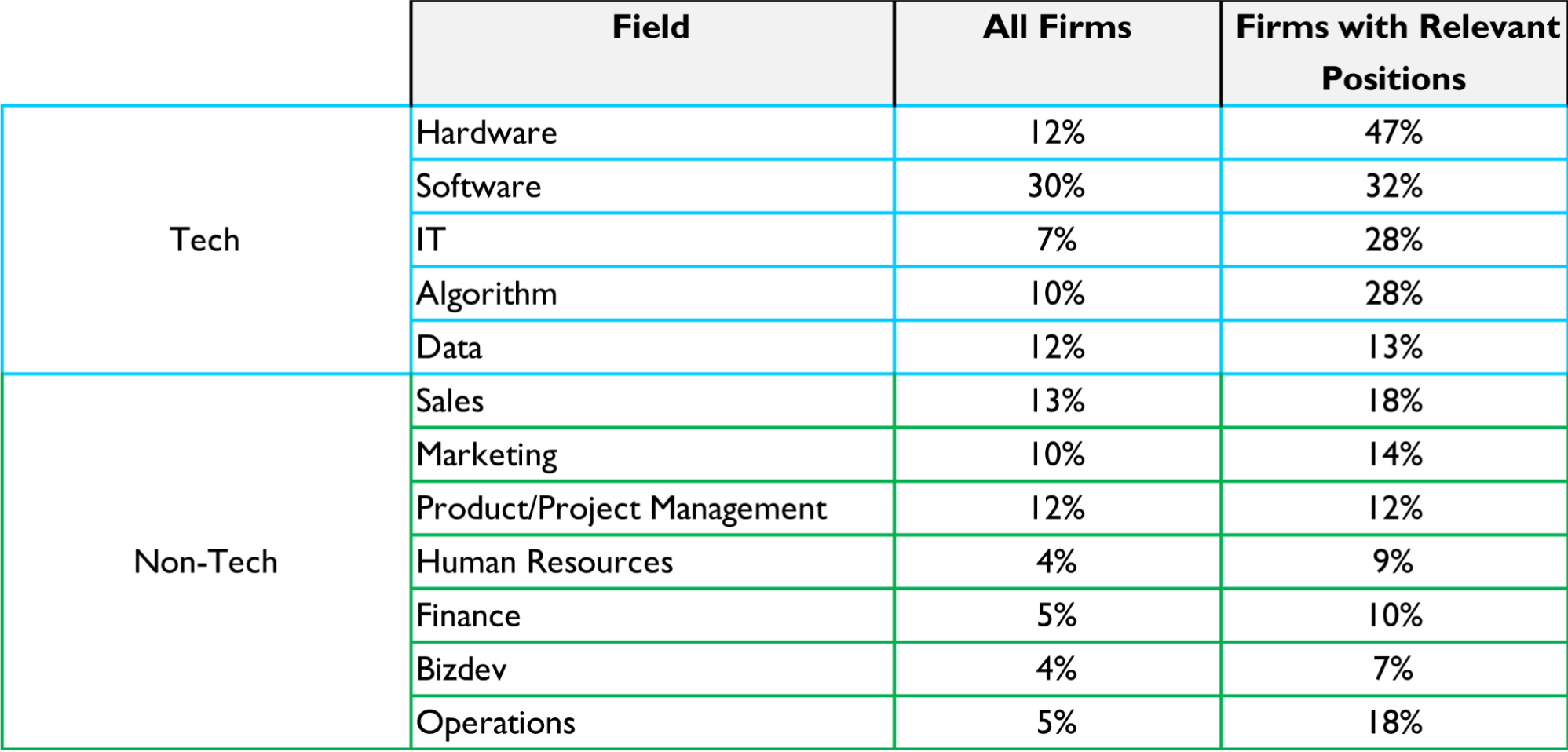

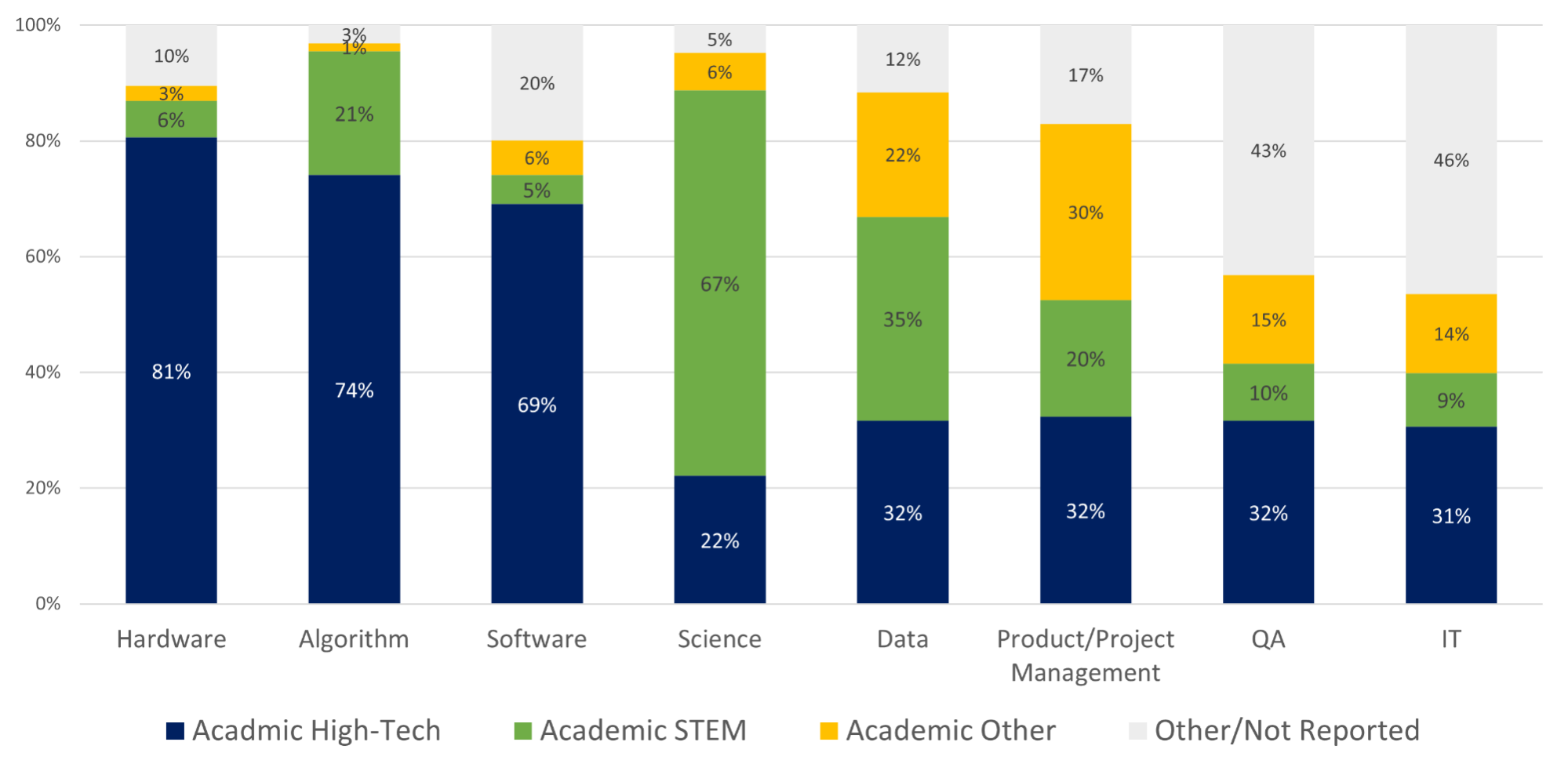

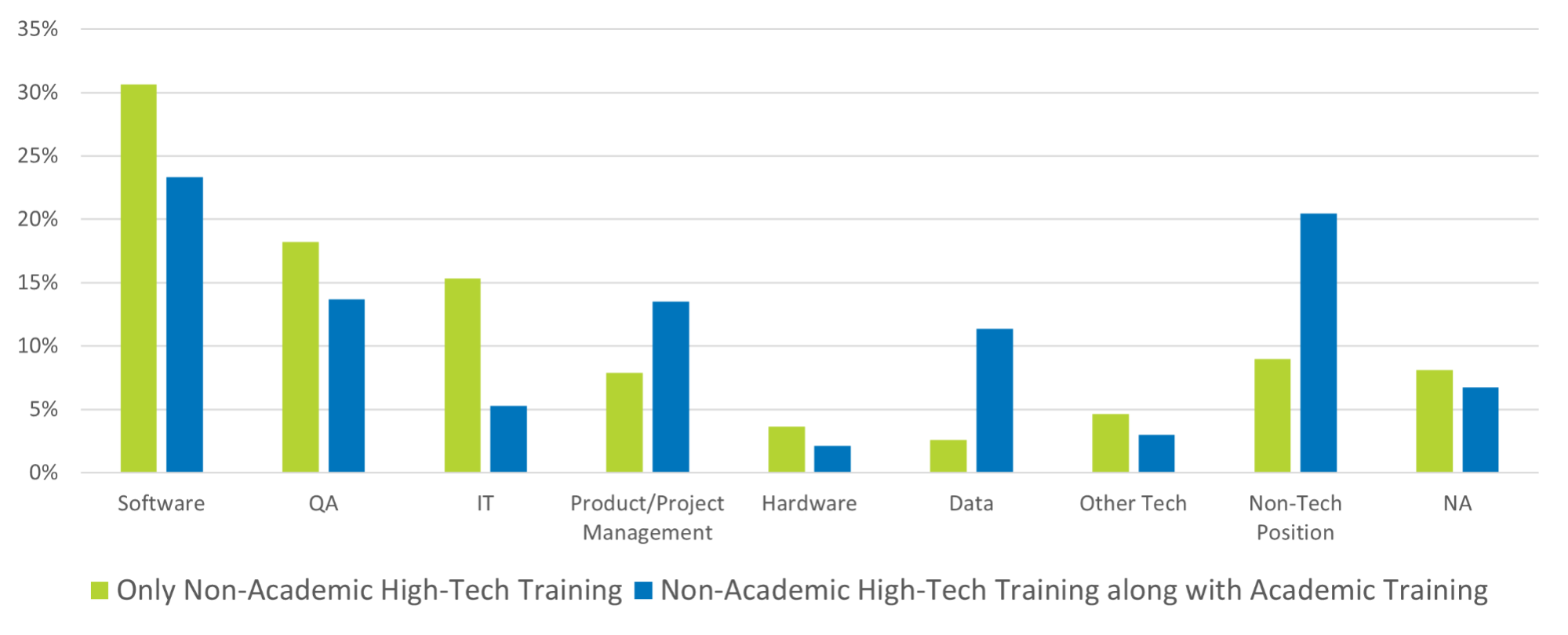

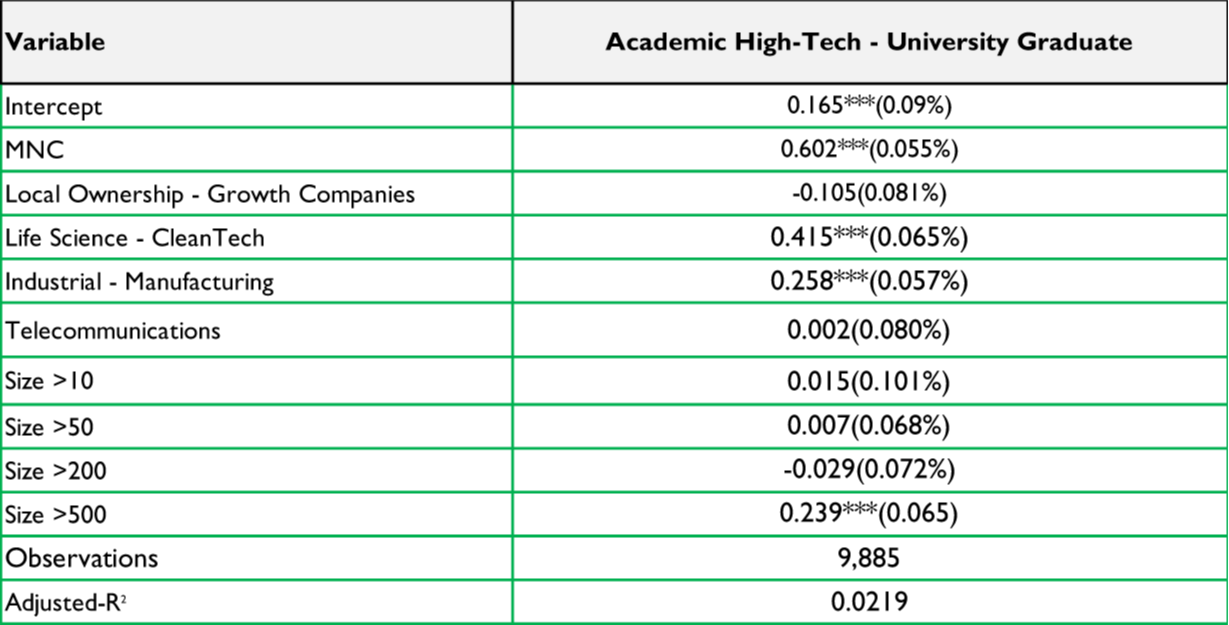

The topic of training is especially important when assessing methods for increasing the supply of human capital in the high-tech sector. This year’s report analyzes, for the first time, data on the connection between types of training and individuals’ first high-tech role. Our main finding is that academic education is still the main entry-point into high-tech. 80% of employees in their first technological role in the high-tech industry have academic degrees; the bigger the company, the higher this rate. This connection strengthens as we approach the roles at the top of the R&D pyramid (i.e., hardware and algorithms).

Naturally, an academic education in a high-tech profession offers an advantage for entering the high-tech industry, especially the R&D centers of multinational corporations. 68% of workers that began working for these centers hold academic degrees in high-tech fields, as opposed to 49% of workers in local companies. In addition, the dominance of universities is still evident: over 60% of new technological workers enter the high-tech industry with university degrees, versus 36% with college degrees (its important to remember that the number of high-tech graduates in recent years is similar for both types of institutions).